Plantar fasciitis is a common running injury that causes a frustrating pain in the sole of the foot or at the heel – it comes in sharp bursts and can make running torture. Typically, the pain is bad in the morning, then eases with warming up, then comes back to “bite” you at rest or the end of the day, sometimes with stiffness in ankle or big toe, too.

Dom Cadden

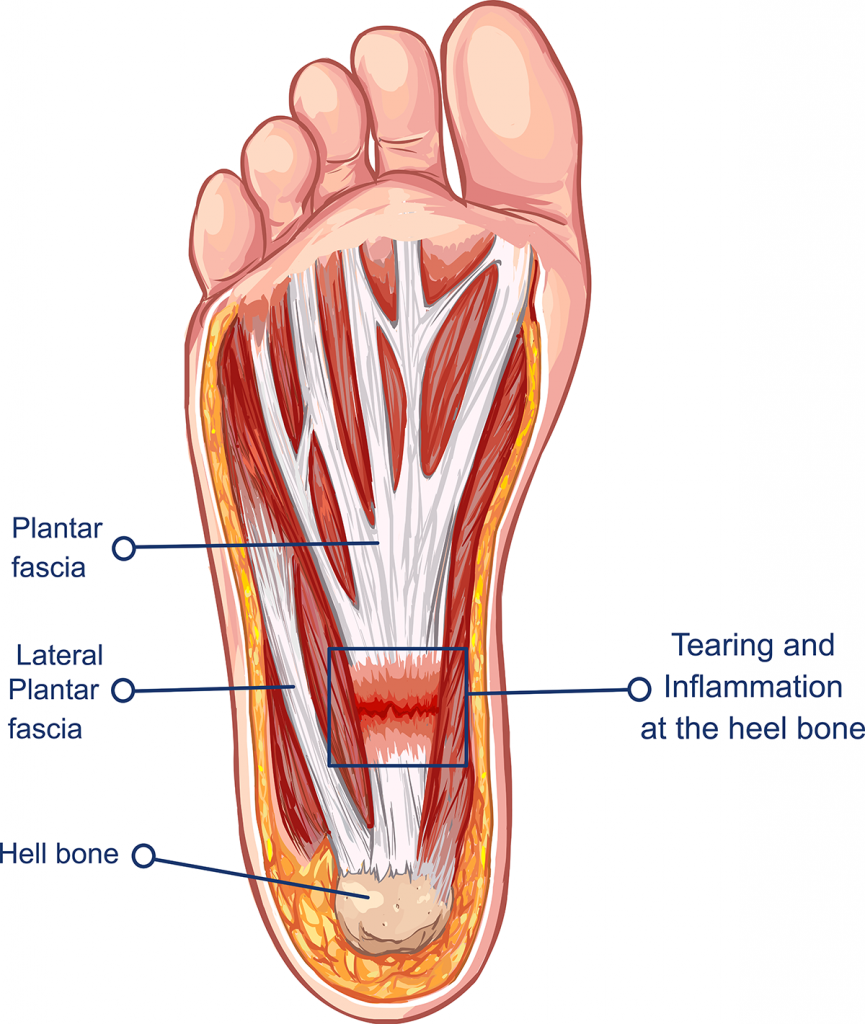

Your plantar fascia is a thick fibrous band of connective tissue that starts under the heel and runs along the sole of the foot towards the toes. It keeps the foot bones and joints in position and enables us to push off from the ground, plus it helps limit how much we can flattening the arch of our foot. Plantar fasciitis occurs when your plantar fascia develops micro-tears or becomes inflamed. This tends to be made worse by bruising (e.g. heel-striking) or overstretching the plantar fascia.

Who tends to get plantar fasciitis?

Other groups with a tendency to get plantar fasciitis include:

- heel strikers

- people with very high or very low arches

- overweight people

- those with tight and inflexible calves and Achilles tendons

- people walking or running barefoot on soft sand for longer than they are ready for

- runners who have moved too quickly to low profile/barefoot-style shoes – before their muscles and ligaments are ready for them.

What causes it?

Podiatry Today (I usually just read it for the pictures) reports that it’s been long believed that reduced ankle dorsiflexion (how much you can lift the top of your foot towards your shin) is the most important risk factor for the development of plantar fasciitis.1

When this combines with a tight Achilles tendon, there’s a tendency to compensate by pronating the foot more (foot rolls inwards and the arch of the foot flattens), which stresses the plantar fasciitis.2

Californian research concluded that tightness or weakness in the soleus can also contribute, since the soleus is used to stop the foot collapsing on impact.

Your shoes might be doing the damage, too. Wearing shoes with poor arch support or stiff soles can be a factor. It’s also important to replace old runners before they stop supporting your feet. A lot of figures get chucked about for shoe lifespan, usually they’re in the range of 650-800km – but the lower the profile, the quicker they wear out.

Preventing plantar fasciitis – what you can do

Use your toes

A team from Canada studying the role of the big toe in running noted a lack of plantar flexion (pushing toes down) at the big toe resulted in a lack of energy generation during the press-off from the ground. This caused more energy to be absorbed and dissipated through the foot, causing more stress on the plantar fascia. They concluded that forcing the big toe downwards primed the lower leg muscles for greater force return and helped protect the foot.

You can work on this by:

- “toe clawing” on carpet

- sprint drills (even if you’re an endurance runner)

- Running on soft sand, where the technique is to clench your toes at the point of impact

- picking up a pencil on the floor with your toes while sitting

- exaggerating the toe push while walking.

Strengthen your soleus

Do some type of calf / toes press exercise for high reps (20+) with a bend at the knee

Avoid heavy heel striking

If you do heel strike, make sure you have a well-cushioned shoe and avoid striking out in front of your hips.

Get the right shoe for you

If you’ve had plantar fascia pain, get proper advice on a shoe has the right heel-to-toe drop for you and the right build for your level of pronation

Stretch right

If you have plantar fascia pain, try these stretches be two times a day, doing each three times, holding the stretch for 40-60 seconds unless too uncomfortable.

Gastrocnemius stretch – stand with both feet flat on floor, one directly in front of the other. Keeping the knee of the back leg straight, lean forward but keep most of your weight on your back foot until you feel the stretch in the calf and Achilles tendon of the back. Vary the distance between the feet to find which one works best for you.

Soleus stretch – do the same as above, but this time bend the back knee – this relaxes the gastrocnemius muscle so you can focus the stretch on the soleus. Lower your body, keeping back upright and most of your weight on your back foot.

Flexor hallicus longus (FHL) stretch – Stand close to a wall or step with your feet one in front of the other. Rest the undersides of the toes of your front foot against a wall/step while your heel remains on the ground. Bend the front knee a little to gently push that knee towards the wall. You should feel a stretch low down in the calf and towards the inside of the shin.

1. Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis: A matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85(5):872-877.

2. Riddle DL, Schappert SM. Volume of ambulatory care visits and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with plantar fasciitis: A national study of medical doctors. Foot Ankle Int. 2004; 25(5):303-310.